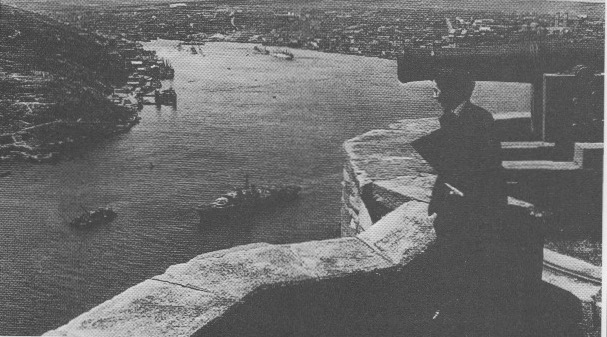

This photograph from Martin Middlebrook’s Convoy, the story of the greatest battle of the North Atlantic between the German U-boats and the allied merchantmen and their escorts, haunted me. The caption read: “A Canadian Wren watches another escort vessal leave St. John’s harbour.” The ship was a corvette, HMCS Bowmanville, visible below the rampart. Being an incurable romantic, or perhaps just endowed with an over-active imagination, I found myself creating a story. Perhaps the Canadian Wren had a lover or husband serving aboard the ship and she was anxiously watching as he sailed away to do battle against the submarine wolf-packs. I knew from reading The Game of Birds and Wolves, by Simon Parkin, that such things actually were possible, that Wrens on shore in naval plotting rooms actually followed the engagements between their men’s ships and the U-boats in what we now term “real time.” So I started searching the internet for information about women in the Royal Canadian Navy during the Second World and found my imagination, as too often, was going a bit too far.

Though I’ve never formally studied art or military history, I’ve managed to acquire a minimal ability to read a painting or a photograph, whether to appreciate the spirituality of Hieronymous Bosch, the humour of William Hogarth, or to determine the subject and authenticity of a scene of battle or of an atrocity. Are the details of the weapons and uniforms authentic for the purported setting? There is a famous photo from the Desert campaign showing what is supposed to be a German soldier surrending to the British at bayonet point—only the man in the German uniform is wearing British army boots!

In the case of the above photo, we might ask how friendly person with a camera happened to pass by just as the ship was passing the narrows. But another photograph retreaved by Google search left my romantic tale in ruins.

Same harbour but no corvette, though the smaller vessal inbound in the first photo may be the same as the one at the base of the bluff. By the position of the ships in the harour, one can tell this photo was taken the same day, probably a few minutes after the first. And obviously it is the same Wren, though posed with a different cannon, a field gun rather than a coastal defence weapon. So we have a couple of posed publicity photos, which explains their presence in the Canadian Defence archive.

Yet I’m glad I tracked down Rosamund Greer’s memoir of her service in the RCN Wrens, joining in 1943 as an 18-year-old. I particularly enjoyed the account of her training at HMCS Conestoga, “the only Naval establishment in the British Navies commanded by a woman” then. Being familiar with Royal Navy terminology, I wasn’t surprised that “His Majesty’s Canadian Ship” was actually a shore installation far from the ocean in Galt, Ontario, an erstwhile reform school for girls. Everything was very closely modelled on British practice, including building named for famous admirals such as Rodney and Nelson. Greer emerges as an utterly charming person, very much an ingenue by contemporary standards. Insturctions in sexual and feminine hygene seem quaint in our time when armed forces supply maternity combat dress. Yet so much cheefulness and patriotism shine through, especially Empire loyalty, as the title reveals. The name HMCS Conestoga puzzled me; I thought of the Oregon Trail rather than Canada. But the author notes that the name came from the wagons used by the early pioneers to Ontario and then of course I recalled that many Empire Loyalists emigrated from Pennsylvania after the American War of Independence, which was the origin of the distinctive pronunciation of “ou” in Canada. Later she served in the Pay Division, stationed in Halifax, the most important Canadian port during the Battle of the Atlantic.

Rosamund Greer died in British Columbia in 2020. You can find her obituary online, with a photo of her in uniform. How I wish I’d encountered her in this life.